Unable to hear himself onstage, Lydon glared at the crowd, half camp, half Antichrist. Though he didn't know it at the time, it was his last day as Rotten for years to come, because McLaren claimed ownership of the name for the next few years. He had twenty dollars in his pocket, no credit card, no airline ticket, no plan -- no future.

Unable to hear himself onstage, Lydon glared at the crowd, half camp, half Antichrist. Though he didn't know it at the time, it was his last day as Rotten for years to come, because McLaren claimed ownership of the name for the next few years. He had twenty dollars in his pocket, no credit card, no airline ticket, no plan -- no future.In other words, the Sex Pistols were being the Sex Pistols, and it was crashing down on them, with the clarity of Rotten's famous last words.

"Ever get the feeling you've been cheated?"

In their twenty-six-month public existence, the Sex Pistols managed one album, a handful of singles, a few dozen club gigs, one mildly profane TV appearance, several arrests, two sackings from record companies, some hasty local bans and one dance fad (the pogo, invented by Sid). When they were scaring the English public, three members lived with their mothers and one lived in a rehearsal space with no hot water because they couldn't afford proper homes; Rotten wrote "God Save the Queen," the band's most notorious song, at his parents' breakfast table, awaiting his baked beans. Their best-played shows drew a couple hundred people or fewer, and even for their last gig, at the cavernous Winterland, they split sixty-seven dollars. They were gone before any of them turned twenty-three.

No one managed to destroy more with less.

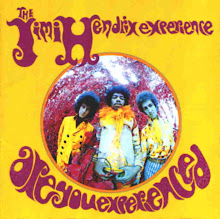

Of their contemporaries, the Buzzcocks wrote better songs, the Ramones were more conceptually perfect and the Clash were less internally conflicted. Siouxsie and the Banshees dressed better. But it is the Pistols who breathed the viral promise that punk's elements, including their own inadequacies, represented something more: a rejection not just of work and rules but of the rebellions of the previous generation, which were then being fed back as a new pleasure industry. "I hate shit," Rotten said in the band's first interview, just four months after their first gig. "I hate hippies and what they stand for. I hate long hair. I hate pub bands. . . . I want people to go out and start something, to see us and start something, or else I'm just wasting my time." He could not have known how far his provocation would carry. When a square British television announcer warned viewers, "Punk rock . . . to many people, it is a bigger threat to our way of life than Russian communism or hyperinflation," even the kitsch proved prophetic: In 1991, thirteen years after the Pistols' breakup, visitors to post-communist Budapest would have seen the graffiti "Sid Vicious!" in Vörösmarty Square, a new youth culture claiming its identity in the freshest language it knew.

Of their contemporaries, the Buzzcocks wrote better songs, the Ramones were more conceptually perfect and the Clash were less internally conflicted. Siouxsie and the Banshees dressed better. But it is the Pistols who breathed the viral promise that punk's elements, including their own inadequacies, represented something more: a rejection not just of work and rules but of the rebellions of the previous generation, which were then being fed back as a new pleasure industry. "I hate shit," Rotten said in the band's first interview, just four months after their first gig. "I hate hippies and what they stand for. I hate long hair. I hate pub bands. . . . I want people to go out and start something, to see us and start something, or else I'm just wasting my time." He could not have known how far his provocation would carry. When a square British television announcer warned viewers, "Punk rock . . . to many people, it is a bigger threat to our way of life than Russian communism or hyperinflation," even the kitsch proved prophetic: In 1991, thirteen years after the Pistols' breakup, visitors to post-communist Budapest would have seen the graffiti "Sid Vicious!" in Vörösmarty Square, a new youth culture claiming its identity in the freshest language it knew.At a cafe in West Hollywood, Steve Jones had his own take on the meaning of the Sex Pistols. It was midafternoon, and he had just finished his daily radio show, Jonesy's Jukebox, with a guest appearance by Slash from Guns n' Roses. Jones wore a black anarchy T-shirt, tired eyes and mild regret that he was lapsing on his resolution to cut down on coffee. "How'd it go with John?" he asked. "Had he been hitting it?" (Lydon for his part had said, affectionately, "Steve thinks thinking's a problem.") Jones has lived in Los Angeles for the last twenty-six years, sober for the last sixteen, but he has little contact with Lydon.

"Do you think it's lame if we go?" he asked, regarding the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. "I think it would be a good thing if we go and play. That would be the most punk thing to do. And just let the swindle continue. I think it's not the punk thing to do to slag it off. That's the obvious thing. That's like the mentality from twenty, thirty years ago. I'm all about making money. I'm not into that about selling out. Sold out? We sold out years ago when we signed with Warner Bros. That's a load of shit. I wanna make some dough. We've never made dough. Everybody else has made dough. Green Day has made millions of dollars off our coattails, and all these other fucks. Which is fine, but I want to make a little dough."

He smiled at the old recurring differences, never resolved. "I hate being in the Sex Pistols," he said, with humor more than malice, like half of a cantankerous older couple. "I just want to lead a nice, easy, normal life now. It's never like that. It's like a dysfunctional family. It's the same shit as any other band. Just that a lot of bands say they don't do that."

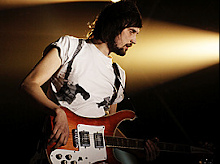

At fifty-one, Jones is keenly attuned to the motion of any female figure on either side of Santa Monica Boulevard and more than willing to share details of his experience with Viagra or the curative powers of amatory dress-up. What he had not shared, until recently, is that even during the Pistols days he secretly preferred colossal mainstream bands like Queen, Boston and Journey to the bands on the punk scene.

In the circus that was the Sex Pistols, Jones and Paul Cook, the drummer, never got the attention that went to John, Sid or Malcolm, and even within the band, they were often demeaned as "the sidemen." But to listen now to Never Mind the Bollocks, Here's the Sex Pistols is to hear the power of their conventional virtues. Now that the songs aren't imperiling the empire, they flat rock.