Fast-paced and kaleidoscopic, Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll has clearly been put together with a respect and devotion that would make Ian Dury grin. Taking us from his shambolic early gigs in pubs to fame, fortune and inevitable decay in a country mansion, the film concentrates on the ever-widening divide between Dury's domestic life with long-suffering wife artist Betty, played by Olivia Williams, and their two small children, and his desperate need for musical affirmation. Directed at breakneck speed by Mat Whitecross (BAFTA nominated for The Road to Guantanamo), much of the action naturally takes place onstage. Dury must be one of the trickier roles to tangle with but Andy Serkis, until now best known as Gollum in The Lord of the Rings, inhabits the man so completely, it's unnerving – from the stumbling walk, result of a childhood bout with polio, to the ravaged Cockney growl that made Burl Ives sound falsetto.

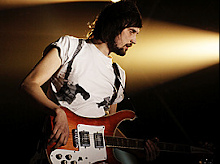

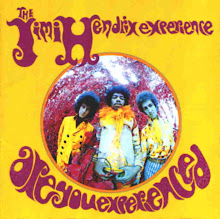

Fast-paced and kaleidoscopic, Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll has clearly been put together with a respect and devotion that would make Ian Dury grin. Taking us from his shambolic early gigs in pubs to fame, fortune and inevitable decay in a country mansion, the film concentrates on the ever-widening divide between Dury's domestic life with long-suffering wife artist Betty, played by Olivia Williams, and their two small children, and his desperate need for musical affirmation. Directed at breakneck speed by Mat Whitecross (BAFTA nominated for The Road to Guantanamo), much of the action naturally takes place onstage. Dury must be one of the trickier roles to tangle with but Andy Serkis, until now best known as Gollum in The Lord of the Rings, inhabits the man so completely, it's unnerving – from the stumbling walk, result of a childhood bout with polio, to the ravaged Cockney growl that made Burl Ives sound falsetto.There's a droll Withnail & I gloom at the start, but the opening credits, courtesy of pop artist Peter Blake, with whom Dury studied at the Royal College of Art, are eye-poppingly psychedelic, taking you right inside the riot of Dury's head. It contrast fits; for anyone in their teens and twenties in late-1970s England, the first bars of Dury’s jaunty top-selling single, Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick – played here, complete with crazed sax solo and anti-violence message – conjure a world of energy, possibility and louche charm, just the ticket in a country stuck deep in recession. As we watch Dury, already a dad, already an ex-art teacher, get kicked off one too many small-time stages and start to motor round defiantly selecting what were to be the Blockheads, that artwork springs up again; next thing you know, Dury's got the mixture right, gurning in that rock 'n' roll vaudeville style, roaring lyrics of such lecherous innuendo, you realise he'd never get a deal these days. Soon he's picked up girlfriend Denise (Naomie Harris) – he didn't call himself Mr Love Pants for nothing – and moved with her out of the family's suburban semi into a decrepit hole in what he liked to call Catshit Mansions. A new life was beginning.

But of course, Dury was nothing if not triumphant underdog, and the film, often dangerously moving, deals with this side of things in detail. Shadowy flashbacks document his efforts to survive the brutish boarding school for the disabled to which he was sent, and the memories of rare visits from his father (played by Ray Winstone), who'd take the young Dury out for idyllic days before returning him to the school and its bullies, many of them teachers. On a return 'celebrity' visit, he learns that one particular teacher has hanged himself, and smiles serenely, 'That's the best news I've had all day.'

But of course, Dury was nothing if not triumphant underdog, and the film, often dangerously moving, deals with this side of things in detail. Shadowy flashbacks document his efforts to survive the brutish boarding school for the disabled to which he was sent, and the memories of rare visits from his father (played by Ray Winstone), who'd take the young Dury out for idyllic days before returning him to the school and its bullies, many of them teachers. On a return 'celebrity' visit, he learns that one particular teacher has hanged himself, and smiles serenely, 'That's the best news I've had all day.'The trouble was, Dury was a deeply selfish bloke, in the way the creatively driven can be. An early scene shows him rehearsing deafeningly while Betty, in the upstairs bedroom, is in labour. It's played for laughs (‘Can you keep the noise down? I’ve just given birth!’), and Dury's crumpling face as he holds the baby shows his tenderness, if it doesn't quite allow for remorse. But this is the man we watch leaving his son in the care of giant bruiser the Sulphate Strangler (actually, a bit of a teddy bear); forgetting birthdays; ignoring a ten-year-old Baxter all the way through a drug-fuelled party. You want to hate this charismatic egotist, quiffed in the manner of hero Gene Vincent, chainsmoking, beer-swilling, flirting but above all sweating over melodies and lyrics – but somehow you can't. The songs it was all for are present and correct, from the title track to Clever Trevor, re-recorded with crunching vim by the original Blockheads and not actually punk at all, though Dury's cited as a founder member and wore razor blade earrings before the idea crossed Johnny Rotten’s mind. No, this was much more complex, a brew of reggae, rock ‘n’ roll and jazz, a bouncing bed for lyrics of hilarious articulacy.

But the subtle mix of dark and light make this much more than a rock biopic. Whether we’re watching a young Dury being knocked to the floor, the estranged husband suavely buckling on callipers after a night of torrid sex or the finally shamed, remorseful father whispering to his son, 'Don't be like me. Be like you...', this is the tale of a vulnerable genius who barrelled through every setback. The film is top and tailed with scenes in the music hall tradition that framed Dury’s life so well, from rakish bravado to underlying melancholy.